|

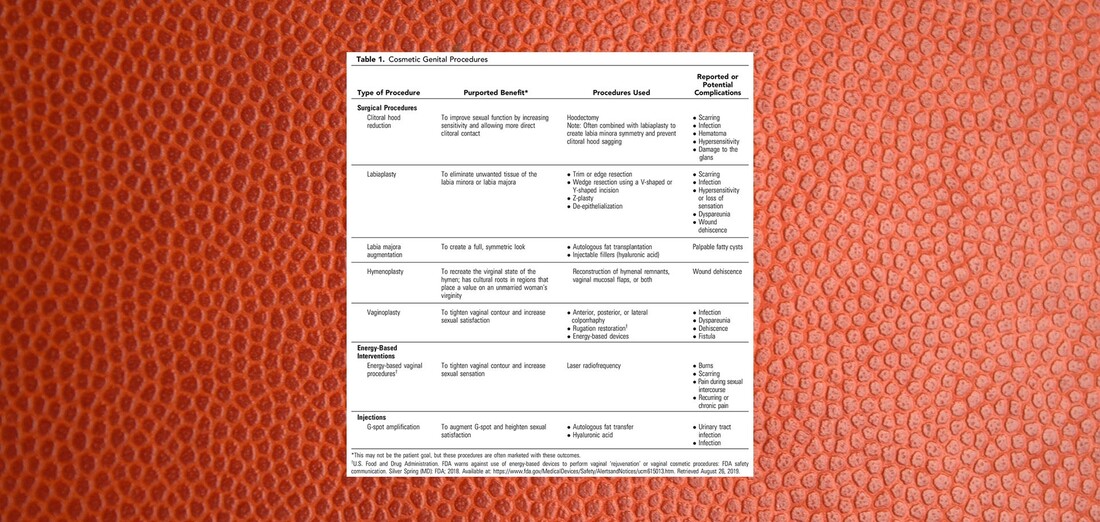

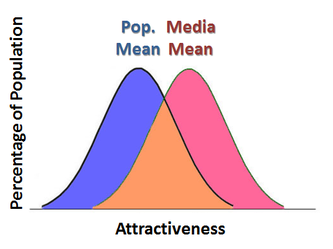

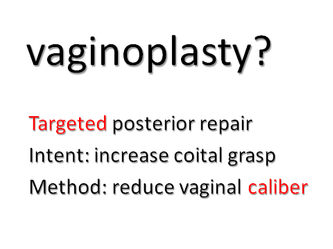

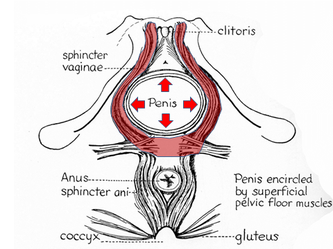

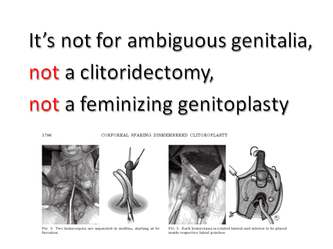

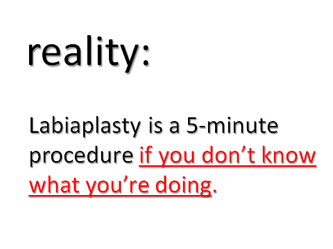

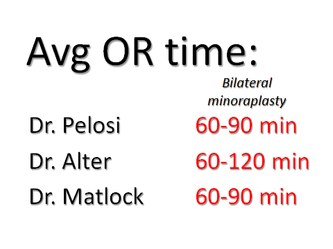

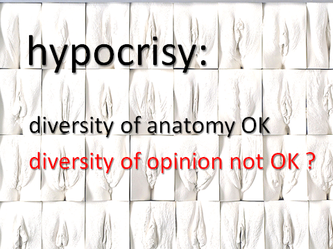

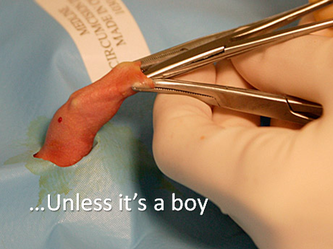

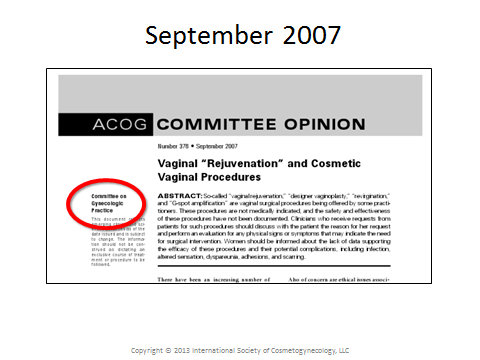

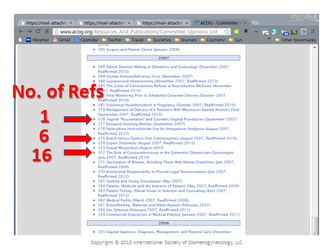

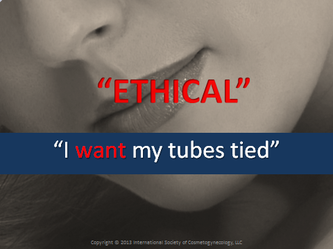

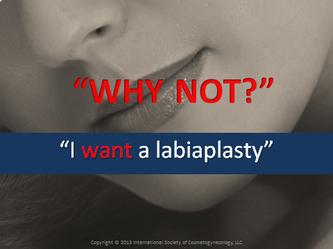

This article was originally published on LinkedIn on December 28, 2019. and it was the transcript of a podcast on The Top Cosmetic Gynecologists released on December 26, 2019. The path of the righteous man is beset on all sides by the inequities of the selfish and the tyranny of evil men. Like that distorted passage that evokes the air of biblical authority from a version of Ezekiel 25:17 that never existed, today’s topic also focuses on a heavily twisted blend of fact and fantasy trying desperately to attain an air of unquestioned authority. A quest that will be stricken down here today. Wearing all of the the lipstick, so to speak, of an authoritative document from an otherwise reliable source, the uninitiated and the casual reader alike might miss the glaring nature of that which they might accidentally embrace. I’ve devoted this essay to the goal of ensuring that this does not happen. A Few Good TermsLet’s button down a few concepts central to our exposé first so that we can roll smoothly and logically. First, let’s define expertise, the state of being an expert of the principles and practice of a body of knowledge. What is an expert? The most common definition of an expert is a person who has a comprehensive and authoritative knowledge of or skill in a particular area. I think you have to have both. By way of example, Tiger Woods is an expert in golf. His coach is not. His coach is an expert in coaching golf, but not necessarily in the skill of actually swinging the clubs. A novice might even beat him. I think that’s a suitable definition of an expert and conveniently, it brings us to the concept of being authoritative. What does it mean to be authoritative? ...or to say that something or someone is authoritative? The most common definition of authoritative is the state of being able to be trusted as being accurate or true. In the legal world, authoritative takes on a slightly different meaning. When one states that a source is authoritative, they are saying that that source takes precedence over others. That’s why lawyers frequently trap those who are legally naïve to state that a given source is authoritative during a deposition. You see in law, the accuracy or the truth of the source don’t matter. What matters is that you said they were true. And if you assumed that a source was true today because it’s true most of the time on most matters on other days, you just turned something that wasn’t true and wasn’t accurate into something that can be used against you in a court of law as if it were true and accurate simply because you trusted them blindly today. Let’s leave the courtroom and visit the field of psychology for our third and final concept before we launch into main event: The Concept of the Halo Effect The Halo Effect is the tendency for positive impressions of a person, company, brand or product in one area to positively influence one's opinion or feelings in other areas. It is a type of cognitive bias. For the today’s purpose, we’re going to refine and sharpen our halo effect to mean that it is the tendency for anyone who is a committee member of a committee of an American college of obstetricians and gynecologists who is an expert in traditional OBGYN subject matter automatically to be thought of as an expert in cosmetic gynecology without training, education or experience in cosmetic gynecology. Let the Games BeginThere is a committee on gynecologic practice in an American college of obstetricians and gynecologists. This committee consists of 31 physicians and 5 allied health professionals who in part and in their self-described mission “develop state-of-the-art commentaries on gynecologic subjects related to clinical management as necessary.” The committee members undergo a personnel churn on a yearly basis for some members and on a longer basis for others. The topics on which they produce statements is dictated by others in the College hierarchy and the production of a statement is a year-long process with more than one in-person meeting of the entire group. I know this because I’ve been there and done that. Of these 36 people, all of whom are the finest people exemplary in their field, all of whom have devoted their careers to the promotion of women’s health, many of whom cater daily to the medical needs of women, many of whom are devoted to the education and development of future women’s healthcare professionals, none have any training, education or experience in cosmetic gynecology. I don’t state this casually. I checked and cross-referenced every single member of this committee against every commonly used term to identify procedures and services in the field of cosmetic gynecology. These people recently published an opinion on cosmetic gynecology entitled Committee Opinion: Female Genital Cosmetic Surgery that includes Recommendations and Conclusions. To summarize so far: A committee of non-experts in cosmetic gynecology From an American college of non-experts in cosmetic gynecology Published an opinion on cosmetic gynecology. Let that sink in... A committee of non-experts in cosmetic gynecology From an American college of non-experts in cosmetic gynecology Published an opinion on cosmetic gynecology devoid of expertise and put forth a series of recommendations and conclusions. Let's take a look at this document in detailLet’s dissect it. Let’s analyze it. And let’s see what type of statement has been concocted by these non-experts in cosmetic gynecology. We will tackle it from beginning to end. I will read sections of the text and give you my impressions at all relevant intervals. For ease of interpretation, I have placed the text from this document in italics for the remainder of this essay. Committee Opinion No. 795 Elective Female Genital Cosmetic Surgery ABSTRACT: “Female genital cosmetic surgery” is a broad term that comprises numerous procedures, including labiaplasty true, clitoral hood reduction true, hymenoplasty true, labia majora augmentation true, vaginoplasty and G-spot amplification. G-spot amplification is not a surgical procedure. Any expert in cosmetic gynecology knows this. Any novice in cosmetic gynecology knows this. Patients know this. So what’s G-spot amplification doing on a list of surgical procedures? There are only two possibilities: Either it was included out of sheer ignorance due to a total lack of experience with the topic of cosmetic gynecology or it was placed there deliberately for reasons unknown. To me, it wreaks of ignorance. Remember, this document is the product of 36 non-experts in cosmetic gynecology sitting around a table. Both patient interest in and performance of cosmetic genital procedures have increased during the past decade. Lack of published studies and standardized nomenclature related to female genital cosmetic surgical procedures and their outcomes translates to a lack of clear information on incidence and prevalence and limited data on risks and benefits. All True. Women should be informed about the lack of high-quality data that support the effectiveness of genital cosmetic surgical procedures and counseled about their potential complications, including pain, bleeding, infection, scarring, adhesions, altered sensation, dyspareunia, and need for reoperation. Sounds good right? It’s got that authoritative tone and a little bit of fear factor tossed in there. Well, not so fast. How do you measure the effectiveness of any cosmetic procedure? Breast? Nose? Cosmetic gyn or anything else? Simple. The patient is happy with her result. Her expectation was met. That can only be measured by asking the patient if she’s happy. If she’s unhappy it’s a total failure. Even if the result was technically perfect. And you can’t measure that with a number. The result is subjective. And subjective data is never high-quality data. It’s opinion all the way and that means that you will never be able to extract high quality data on the effectiveness of any cosmetic procedure Whether it’s breast, nose, cosmetic gyn, tummy tuck, facelift, liposuction or anything else. It’s always going to boil down to patient satisfaction. Any expert in cosmetic gynecology or cosmetic surgery in general knows this. Furthermore, even if we had the highest quality level 1 evidence on the subjective endpoint of making women happy in some imaginary world, it’s non-transferable. No two women have the same expectation of what will or won’t make them happy. Just because 99 percent of women were happy with procedure X doesn’t mean that the next patient that walks through the door will be happy. Setting the expectation, which wasn’t addressed all in this document, would be central to this process. Let’s take a look at the second part of the statement that women should be counseled about the potential complications. Yes. It’s always a good idea to review the risks of a procedure any procedure with the patient. It’s part of any informed consent process anywhere in the world. However and apparently, when they talk about potential complications, they are no longer concerned about the lack of high quality data on potential complications. “Potential complications” gets a free ride on that because it’s negative. It’s anti cosmetic surgery. It’s there to create fear. Now, don’t get me wrong, these potential complications are real. But they are extremely rare in the hands of trained, educated and experienced cosmetic gynecologists. So if you really want to make a statement that doesn’t sound like fake news, you need to wake up to the reality that there is an entire world of expert cosmetic gynecologists who treat women every day and rarely see these issues. I counsel my patients that these issues that non-experts bark about are definitely a real and present danger in the hands of nonexperts, but not mine where they are rare. And I have over two decades of experience to show for it. And so do my expert colleagues. But we weren’t consulted. And I know that they know who I am, where I am, and how to reach me and my expert colleagues. It is very unusual that no experts in cosmetic gynecology were recruited as subject matter experts to be a part of this committee. I can’t think of any industry or professional endeavor in which bringing in an expert wouldn’t be viewed as essential to producing a professional level statement. Obstetrician–gynecologists should have sufficient training to recognize women with sexual function disorders as well as those with depression, anxiety, and other psychiatric conditions. Individuals should be assessed, if indicated, for body dysmorphic disorder. In women who have suspected psychological concerns, a referral for evaluation should occur before considering surgery. This is an excellent recommendation. I would add, from my vast experience, that it is common for patients with body dysmorphic disorders to seek out providers of cosmetic surgery and that the prevalence of such patients is higher than the prevalence of this condition in the general population. As for all procedures, obstetrician–gynecologists who perform genital cosmetic surgical procedures should inform prospective patients about their experience and surgical outcomes. YES! I addressed this above. The surgical experience and outcomes of the individual surgeon is the only thing that matters in the individual case. My expertise is not your expertise. My excellent results don’t imply that others will necessarily have similar results unless they practice at a similar level with similar techniques. Patients should be made aware that surgery or procedures to alter sexual appearance or function are not medically indicated, pose substantial risk, and their safety and effectiveness have not been established. (excluding procedures performed for clinical indications, such as clinically diagnosed female sexual dysfunction, pain with intercourse, interference in athletic activities, previous obstetric or straddle injury, reversing female genital cutting, vaginal prolapse, incontinence, or gender affirmation surgery). This is the craziest statement of all. When I titled this essay Lipstick on a Pig, this is the Pig. There are two huge glaring warts on this pig. The first is a fatal flaw in logic: the statement says that all things being equal, the safety and effectiveness of a surgical procedure hinges on whether it is clinically indicated or not based on their desperate list of “clinical indications” that seems to have been jammed into the document at the last minute. By this twisted reasoning, if a pair of identical twins underwent labiaplasty – one sister for pain and the other for cosmetic effect, one would be at higher risk for complications than the other. That is insanity. I’m not making this up. I’m reading it from this “state-of-the-art commentary”. But that’s not all. When they provide a list of procedures that are excluded from attack because they are clinically indicated, they don’t provide ANY clinical data that their list of of procedures that are excluded from attack are safe or effective. They’re asking you to give them a free pass. The second wart on this pig, is their statement that these procedures pose not just a risk, but rather a substantial risk. They used the word substantial. Substantial is not a benign word. Substantial is a very dangerous word. Substantial means large. And large speaks to data. And when there is no data anywhere in this document or in the references of this document that shows large risk associated with cosmetic surgery …and you know this, then you are telling me that you don’t really care about data. You are showing me that you have an agenda and that you care more about that agenda than you care about data. And if you produce a pernicious, mendacious unsubstantiated declaration in the age of transparency, you can’t hide. I’ve seen the credentials of every single person on this committee. I know what they know and I know what they don’t know. I know when they’re telling the truth and I know when they’re…let’s call it speculating to be polite. Recommendations and Conclusions The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists makes the following recommendations and conclusions regarding the use of and indications for female genital cosmetic surgery. Remember, these people are not experts in cosmetic gynecology. They have no training, no education and no experience in this field. • Patients should be made aware that surgery or procedures to alter sexual appearance or function (excluding procedures performed for clinical indications, such as clinically diagnosed female sexual dysfunction, pain with intercourse, interference in athletic activities, previous obstetric or straddle injury, reversing female genital cutting, vaginal prolapse, incontinence, or gender affirmation surgery) are not medically indicated, pose substantial risk, and their safety and effectiveness have not been established. We just discussed the illogic of this statement a few minutes ago. Cosmetic surgery is never medically indicated, but you can’t use the word Substantial when talking about the risk if you don’t have any data to prove it. From the tone you would think that there’s a pile of burning bodies and a wake of devastation as if a Mongol Horde had swept through the female population. And what’s going to happen if we don’t nip this nonsense in the bud is that those who don’t know a thing about cosmetic gynecology, those who assume that everything that comes of out the American College of Non-Experts in Cosmetic Gynecology is automatically correct are going to start to believe it. And when they start to believe it, you’re going to have to stand your ground and defend your livelihood from these misguided souls screaming mindlessly that cosmetic gynecology carries substantial risks. So if you value your business, get out there and start poking holes in these weak arguments fiercely and frequently. I’m giving you fair warning. You cannot stand by and watch. You must take control. • Women should be informed about the lack of high-quality data that support the effectiveness of genital cosmetic surgical procedures and counseled about their potential complications, including pain, bleeding, infection, scarring, adhesions, altered sensation, dyspareunia, and need for reoperation. We covered this already too. When effectiveness is measured subjectively, when it is the opinion of the patient whether her expectation was met, you will never have high quality data. That being the case, the bar for effectiveness for cosmetic gyn surgery is the same as that for breast augmentation, face lifts, rhinoplasty, tummy tucks and body contouring and the rest of the medical world doesn’t have a problem with that. We also discussed the association between expertise and a low risk of complications and a lack of expertise and a high risk of complications. • Obstetrician–gynecologists should have sufficient training to recognize women with sexual function disorders as well as those with depression, anxiety, and other psychiatric conditions. Individuals should be assessed, if indicated, for body dysmorphic disorder. In women who have suspected psychological concerns, a referral for evaluation should occur before considering surgery. This is true. It’s one of the few recommendations that’s grounded in reality and it is extremely important to keep a sharp eye out for those who have mental issues. • In responding to a patient’s concern about the appearance of her external genitalia, the obstetrician–gynecologist can reassure her that the size, shape, and color of the external genitalia vary considerably from woman to woman. These variations are further modified by pubertal maturity, aging, anatomic changes resulting from childbirth, and atrophic changes associated with menopause or hypoestrogenism, or both. I don’t know where they’re going with this here. Telling a woman who seeks out a cosmetic procedure that she’s normal makes sense if she’s doing it because she thinks it’s abnormal, but that’s really something in the psychological screening process. Almost all patients seeking cosmetic procedures have normal anatomy whether it’s cosmetic gyn, breast augmentation, facelifts, tummy tucks, or anything else. But having normal anatomy is not a reason enough to decline the request unless the request cannot be performed for technical reasons related to the specifics of her anatomy. Inconveniently true is the fact that tubal ligations, circumcisions and abortions are routinely performed on normal anatomy by members of the Committee. • As for all procedures, obstetrician–gynecologists who perform genital cosmetic surgical procedures should inform prospective patients about their experience and surgical outcomes. This is a statement that we addressed previously and that is certainly valid. • Advertisements in any media must be accurate and not misleading or deceptive. There’s nothing wrong with calling for truth in advertising, but this advice should apply equally to anything and everything in the field of obstetrics and gynecology. “Rebranding” existing surgical procedures (many of which are similar to, if not the same as, the traditional anterior and posterior colporrhaphy) and marketing them as new cosmetic vaginal procedures is misleading. If I were to rebrand a traditional anterior or posterior colporrhaphy as a procedure to tighten the vagina – a vaginoplasty, I – one of the world’s experts in vaginoplasty - would not achieve a tighter vagina. Many of the patients that I operate for vaginal tightening have had traditional anterior and posterior colporrhaphies and they come to me and my expert colleagues precisely because we use techniques that are distinct from these procedures. They might address the same anatomy, they might involve similar dissections and similar tools, but they are miles apart in both intent and effect. Of course, a committee of non-experts wouldn’t know that. Background Female genital cosmetic surgery, when referred to in this Committee Opinion, is defined as the surgical alteration of the vulvovaginal anatomy intended for cosmesis in women who have no apparent structural or functional abnormality. Genital cosmetic surgery will not refer to procedures performed for clinical indications (eg, clinically diagnosed female sexual dysfunction, pain with intercourse, interference in athletic activities, previous obstetric or straddle injury, reversing female genital cutting, vaginal prolapse, incontinence, or gender affirmation surgery). The goals of this Committee Opinion are to provide the following three items: 1) potential reasons for the increase in the number of cosmetic genital surgical procedures; 2) a brief overview of cosmetic vaginal procedures and outcomes data associated with them; and 3) an opinion on their use for the sole purposes of cosmesis, sexual function augmentation, or both. This Committee Opinion has been updated to include new data on elective female genital cosmetic procedures and their outcomes, as well as guidance on patient counseling. For guidance on labial surgery in adolescents, see Committee Opinion No. 686, Breast and Labial Surgery in Adolescents (1). Both patient interest in and performance of cosmetic genital procedures have increased during the past decade. For example, labiaplasty rates in the United States increased more than 50% between 2014 and 2018 (2). The next statement is a paragraph that starts with a false statement: At the same time, ethical and, more recently, safety concerns have been raised about the performance of cosmetic genital surgery. The reason that it’s false is that ethical and safety concerns about cosmetic genital surgery have NOT recently been raised. Their attempt to support this statement is also false. They say the following: In July 2018, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warning against the use of energy-based devices (most commonly, radiofrequency or laser) outside of standardized research protocols for cosmetic vaginal procedures or vaginal “rejuvenation,” citing their potential for serious adverse events, including vaginal burns, scarring, pain during sexual intercourse, and recurring or chronic pain (3). That statement is a misquote of the actual FDA statement on which I wrote an in depth LinkedIn article last year when it first came out. They are trying to gaslight the reader – to mischaracterize past events to suit an ulterior purpose. The real FDA statement mentioned nothing about “standardized research protocols” or any language to that effect. The real FDA statement was directed at inappropriate marketing by the medical industry and not at clinicians. The real FDA statement said nothing about cosmetic genital surgery. The entire statement was about NON-surgical energy based devices for NON-surgical procedures. So the last place that it belongs is in document about surgical procedures. Any expert in cosmetic gynecology would know this. Potential Reasons for Increased Interest in Genital Cosmetic Surgery Shaving, waxing, electrolysis, and laser removal of pubic hair may allow a better view of the external genitalia for both women and their partners. In a cross-sectional study of more than 2,400 women aged 18–68 years living in the United States, 79% had partially or totally removed their pubic hair or were hair-free in the past month (4). One consequence of this procedure may be to draw more attention to asymmetries and differences in the external genitalia, potentially contributing to an increased desire for surgical alteration (5). I agree with this completely. It’s a change in the culture that started sometime in the 1990s and is currently the norm. Every gynecologist that I know say the same the thing. The perception of having aesthetically inferior external genitalia, augmented by the internet, online pornography, and other media sources, may drive women to seek surgical alteration (6). I pulled this reference. It was a review of 5 papers from outside the US from 2010-2012. Nowhere in this reference is the term “aesthetically inferior” used. The term “aesthetically unpleasing” is used instead. It’s significant. Also significant is that this paper only looked at content on a few foreign websites and nowhere in this paper did they ever collect or seek to collect any data on whether these websites had any effect at all on driving women to seek anything. For the record, the patients who seek me out for labiaplasty and other aesthetic procedures don’t come in because they feel inferior. They either personally dislike their appearance or feel physical discomfort. Women who explore cosmetic surgery often turn to internet searches. This should shock no one. We live in the age of internet searches for everything. I do it , you do it, it’s the world we live in. This is particularly important because the internet may be their only source of information (6). There is nothing in this reference that supports this statement. It was an analysis of websites not a survey of patients as to where they get their information. So it’s an opinion, but it’s presented as fact and that’s not being transparent. Also, it’s about to be contradicted in a the next section of the document by their next reference. A systematic review of online content that promoted female genital cosmetic surgery found that sites that promoted cosmetic genital surgery regularly described the wide variation of normal vulvar appearance as unnatural or diseased and implied that variation beyond the prepubescent-looking vulva (eg, no visible labia minora, narrow vaginal opening) results in distress and sexual dysfunction (6). This is reference #6 again which was a study of 5 papers covering a handful of websites of which were outside the USA (UK, Netherlands, Nigeria, Australia) In a cross-sectional survey of 395 participants, older women (45–72 years of age) were more likely to consider cosmetic genital surgery than a cohort of younger women (18–44 years) (7); this is not surprising given the societal emphasis on reversing the effects of normal aging. I pulled this reference too. And I found a few interesting things: First, the survey wasn’t validated. That means we can’t be sure that the women understood the questions adequately to give reliable answers. Second, and case in point, the question in the survey that asked about considering cosmetic surgery didn’t specify that it had to be genital surgery as our committee statement is trying to imply. Third, over 90 percent of all of the women in the study thought their vulva was normal. Finally, the women in this study said they got the majority of their information about the appearance of their vulva from their doctor #1 and women's magazines and anatomy books and not from the internet. There’s your contradiction to what was said previously when they said women get their information on this topic exclusively from the internet. I guess they didn’t expect the reader to check the references. In a prospective study of 33 women who sought labial reduction surgery at a London gynecology clinic, dissatisfaction with appearance was most commonly reported. For the entire cohort, however, the dimensions of the labia minora measured within the range of typical variability (8). We’ve already stated that cosmetic surgery is almost always done upon normal anatomy and explained the hypocrisy that exists in singling out surgery on this normal anatomy while ignoring cosmetic surgery performed on other normal anatomy elsewhere on the body and gynecologic surgery such as abortions and tubal ligations performed in the pelvis. Of equal importance are marketing claims that genital cosmetic surgery treats cosmetic and functional issues and enhances sexual satisfaction. Well in the case of vaginoplasty to correct vaginal laxity it certainly does and that’s the only surgical procedure aimed at improving sexual function. Again, anyone with experience in cosmetic gynecology knows this. Much of the increase in popularity seen in vulvovaginal procedures for nonmedical indications is associated with the success of direct-to-consumer marketing in the 1990s (9, 10). They reference this statement with a couple of poorly written papers written by anti-cosmetic surgery proponents with a stated radical agenda. In 2013, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists recommended, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists agrees, that women should be given accurate information about normal variations in genital anatomy and that advertisement of female genital cosmetic surgery should not mislead women on what is considered to be normal or what is possible with surgery (11). Characterizing normal anatomic variation as necessitating medical intervention exposes otherwise healthy women to unnecessary surgery with the potential for serious complications. This is all good and well despite their lack of expertise on cosmetic gynecology, but they miss the point completely that cosmetic surgery is always a choice and never a necessity. Additionally, industry-generated conditions and diagnoses, where a proprietary device is deceptively marketed as a proven treatment, are concerning (12, 13). This sentence is another reference to the FDA’s critique of the medical device industry on the marketing of nonsurgical devices for nonsurgical procedures. This entire article is supposed to be about surgery and this snippet of information has nothing to do with surgery. Outcomes of Cosmetic Gynecology Surgery “Female genital cosmetic surgery” is a broad term that comprises numerous procedures, including labiaplasty, clitoral hood reduction, hymenoplasty, labia majora augmentation, vaginoplasty, and G-spot amplification; I mentioned much earlier that G spot amplification is not a surgical procedure and that only someone with a complete lack of knowledge in cosmetic gynecology would not know this. Then they ask you to see Table 1 for descriptions of surgical techniques and complications. Putting bad information into a table makes it look pretty, but it doesn’t magically turn it into better information. Aside from labiaplasty, it is difficult to know how often these procedures are being performed. Lack of published studies and standardized nomenclature related to female genital cosmetic surgical procedures and their outcomes translates to a lack of clear information on incidence and prevalence and limited data on risks and benefits. In general, the safety and effectiveness of these elective procedures have not been well documented, and evidence largely is restricted to clinical case reports and retrospective studies. Measures used to assess outcomes, such as patient questionnaires, are rarely comparable across studies, and follow-up rates vary widely (14). All of this is true and the problem with nomenclature is something that I have addressed frequently in lectures and most recently on episode 20 of this podcast in the context of vaginal laxity. Reports of patient satisfaction should not serve as evidence that these procedures are clinically effective (15). Actually, for cosmetic procedures, patient satisfaction is the only outcome that matters and that can only be measured by questionnaires. Labiaplasty is the most commonly performed cosmetic genital surgical procedure, and a variety of techniques have been described (Table 1). Clitoral hood reduction frequently is performed at the time of labiaplasty to reduce the occurrence of clitoral hood sagging after labiaplasty alone. In a multicenter retrospective cohort study of 258 women who underwent 341 cosmetic genital procedures, 177 underwent labiaplasty, clitoral hood reduction, or both (16). Although this study reported high patient satisfaction and enhancement in sexual function, these results should be interpreted with extreme caution given the lack of a comparison group and use of poorly constructed questionnaires, none of which were validated. Although validated scales were used in the same author’s 2016 prospective cohort case-controlled study of 120 individuals, only 54% of the women having genital cosmetic surgery chose to complete the scale at entry, versus 76% of controls (17). Even with greater use of validated scales in more recent literature, comparability remains difficult with the rare use of the same scale in more than one study. Do you see the game they’re playing here: When you give them data, and it supports that women are satisfied with cosmetic gyn surgery, they tell you that the data is no good When they find even the weakest shred of even a hint of unsubstantiated and sometimes even imagined negativity toward cosmetic gyn surgery, they give it massive importance and drama that it doesn’t deserve and start throwing around phrases like substantial risk. The next item in the article is Table 1 entitled Cosmetic Genital Procedures The bottom half of the table lists nonsurgical procedures and doesn’t belong in an article on surgery.

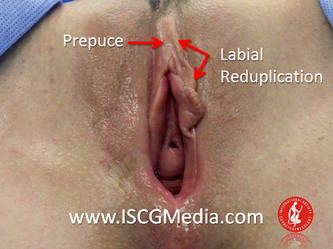

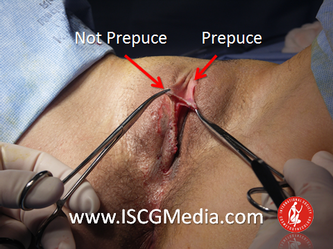

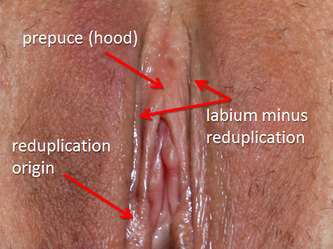

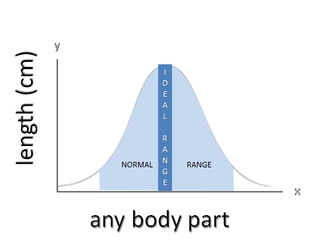

There is a column entitled Reported OR Potential Complications Do you know the difference in meaning between the word "reported" and the word "potential"? I do. Reported means real and potential means possible and possible can mean imaginary and never happened And if you title a column Reported OR Potential, you can stuff whatever you want underneath it even if everything in that column is imaginary and never happened. Pretty convenient stuff. Procedures that focus on the vaginal canal are marketed to improve sexual function. One of the most controversial female genital cosmetic surgical procedures, vaginal “rejuvenation,” is a proprietary term meant to encompass perineoplasty, vaginoplasty, or both, as a technique to reduce the diameter of the vagina, strengthen the perineal body, and enhance sexual function (18). The surgical technique used is very similar, if not identical, to anterior or posterior colporrhaphy and often is combined with perineoplasty. This is a twisted statement full of contradictions and the authors being non-experts in cosmetic gynecology are confused. First, the only controversy surrounding the term vaginal rejuvenation is its meaning. It is vague and has no meaning. Even experts in cosmetic gynecology don’t use this term to refer to a specific operation. Second, the authors seem to be speaking about vaginoplasty – the vaginal tightening surgery - in their critique on its ability to improve sexual function which is a poor choice of words on their part. The function of sex is reproduction. A better phrase, one that an expert would use, would be to improve sexual friction by reducing laxity. Third, they think that a vaginoplasty of this type is “very similar, if not identical to anterior and posterior colporrhaphy”. This statement makes me laugh the loudest because only someone who has never seen a vaginoplasty would ever say that. And anyone who has ever tried to tighten a vagina with a standard AP repair would never have a happy patient if they tried. I know this, I fix the sequelae of these misguided attempts by non-experts regularly. Another method for treating vaginal laxity, described as vaginal rugation restoration, involves use of the CO2 laser to create vaginal rugae in women in whom absent or decreased vaginal rugation has been diagnosed. Scant information on the outcomes (risks and benefits) of laser assistance, rugation restoration, or G-spot amplification exists in the peer-reviewed literature, and the published data are mostly restricted to expert opinion, case reports, or small case series (19). A 2012 prospective observational study of vaginal rugation restoration included only 10 women who underwent the procedure, making it difficult to draw conclusions (20). I don’t know why they decided to give vaginal rugation so much space in this article. I know the long-retired author of the only two papers ever written on this, I know the papers, and I know that very very few people use this technique and those that do use it don’t use it as a treatment for vaginal laxity. So if they wish to attack vaginal rugation, they are attacking a handful of people doing a handful of procedures that don’t really represent the common procedures of cosmetic gynecology. Once again, any expert in cosmetic gynecology knows this. The next statement is one we threw out already because it’s about nonsurgical energy based devices and the authors didn’t know that these are nonsurgical treatments: The FDA’s 2018 Safety Communication warned against the use of energy-based devices (commonly radiofrequency or laser) to perform vaginal "rejuvenation," cosmetic vaginal procedures, or nonsurgical vaginal procedures to treat symptoms related to menopause, urinary incontinence, or sexual function (3). Prospective studies that used validated measures of quality of life, body image, and sexual function are needed to understand the true benefits and harms of these procedures. That’s a great idea. Research should be conducted by those without a financial interest in the outcomes (14). Patient Counseling Understanding a woman’s motivation for cosmetic surgery requires careful and sensitive exploration to ensure her autonomy and rule out the possibility of coercion or exploitation by another person, such as a partner or family member. See ACOG Committee Opinions No. 578, Elective Surgery and Patient Choice, No. 390, Ethical Decision Making in Obstetrics and Gynecology, and No. 787, Human Trafficking (21-23). Labiaplasty in girls younger than 18 years should be considered only in those with significant congenital malformation, or persistent symptoms that the physician believes are caused directly by labial anatomy, or both. Surgical alteration of the labia that is not necessary to the health of the patient, who is younger than 18 years, is a violation of federal criminal law (24) (Box 1). At least one half of the states also have laws criminalizing labiaplasty under certain circumstances, and some of these laws apply to minors and adults. Obstetrician–gynecologists should be aware of federal and state laws that affect this and similar procedures in adolescents (1) and adults. Now, this is a cheap scare tactic placed here to give the impression that you're going to go to jail if you perform a labiaplasty. The laws that are on the books are speaking to female circumcision, infibulation, and ritualistic practices done against a person's will outside of legitimate medicine. They are not targeting labiaplasties and the majority of labiaplasties are not done in the pediatric population. It's an insignificant point that they're trying to make as if the surgeon is going to be criminalized for doing these procedures. Any lawyer will tell you this is nonsense. Obstetrician–gynecologists should have sufficient training to recognize women with sexual function disorders as well as those with depression, anxiety, and other psychiatric conditions. Individuals should be assessed, if indicated, for body dysmorphic disorder, criteria for which, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, include a preoccupation with an imagined physical defect or exaggerated concern about a physical defect that would not be apparent to the casual observer, or a history of repetitive or obsessive behaviors (such as repeated examination or attempts to conceal the flaw, or continually seeking reassurance from others) (25, 26). In women who have suspected psychological concerns, a referral for evaluation should occur before considering surgery (27). These points were discussed earlier and require no additional commentary. They are valid. In responding to a patient’s concern about the appearance of her external genitalia, the obstetrician–gynecologist can reassure her that the size, shape, and color of the external genitalia vary considerably from woman to woman. These variations are further modified by pubertal maturity, aging, anatomic changes resulting from childbirth, and atrophic changes associated with menopause or hypoestrogenism, or both. Although labia minora longer than 30–40 mm is currently marketed as hypertrophic, in a study of 657 adolescent and adult females, the mean length of the labia minora (measured from clitoris to the lower margin of the labia) exceeded that estimate in more than 50% of the individuals (28). Measurements of the external genitalia must be interpreted on an individual basis, and age-related differences in the length of the labia minora vary widely (28). Table 2 provides information on the variability of female genitalia that can be used to counsel patients; however, the values should not be used to determine surgical appropriateness. Although patients often believe female genital cosmetic surgery will improve sexual function, current evidence does not support improvement in body image, libido, or sexual satisfaction. Concerns regarding sexual satisfaction may be addressed by careful evaluation for any sexual dysfunction, relationship issues, and an exploration of nonsurgical interventions, including counseling. For more information, see Practice Bulletin No. 213, Female Sexual Dysfunction (29). This entire section is an attempt to convince you to convince the patient out of having surgery for their own aesthetic concerns if their anatomy is normal. This is absurd because you wouldn't do this to someone who wanted a breast augmentation, a nose job, or any other cosmetic procedure. It is important to review patients’ expectations about the results of surgical intervention. Women should be informed about the lack of high-quality data that support the effectiveness of genital cosmetic surgical procedures and counseled about their potential complications, including pain, bleeding, infection, scarring, adhesions, altered sensation, dyspareunia, and need for reoperation. The possibility of dissatisfaction with cosmetic results, including potential adverse effects on sexual function, also should be discussed. A focus on patient expectations is critical to the success of any cosmetic procedure. If it's realistic and you can achieve it, the patient will be happy. However, if it's unrealistic, you're going to have a problem, she's going to have a problem, and you're never going to be able to achieve an acceptable result with an unrealistic patient. As for all procedures, obstetrician–gynecologists who perform genital cosmetic surgical procedures should inform prospective patients about their experience and surgical outcomes. Advertisements in any media must be accurate and not misleading or deceptive (30). “Rebranding” existing surgical procedures (many of which are similar to, if not the same as, the traditional anterior and posterior colporrhaphy) and marketing them as new cosmetic vaginal procedures is misleading. This entire rebranding concern is a misconception on the part of the authors because they know nothing about the nature of the cosmetic procedures. They seem to think that we are taking standard gynecologic operations, calling them cosmetic procedures, and then proceeding with traditional operations which is clearly not the case. Training Obstetrician–gynecologists who perform cosmetic procedures should be adequately trained, experienced, and clinically competent to perform the procedure (31). Extensive familiarity with appearance and function, as well as the ability to manage complications, are expected from obstetrician–gynecologists who perform these procedures. This was my favorite section and, in my opinion, the only thing of value in the entire document. The points made are obvious, but it would have been much better if they consulted with experts who could have given further guidance on how training and education and experience is obtained in light of the fact that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists doesn't have that ability. Conclusion Obstetrician–gynecologists may receive requests from adolescents and adults for cosmetic genital surgery. For those choosing to provide cosmetic services, patient counseling (including definitions of normal range of anatomy and sexual function), shared decision making, and informed consent are paramount. Patients should be made aware that surgery or procedures to alter sexual appearance or function (excluding procedures performed for clinical indications, such as clinically diagnosed female sexual dysfunction, pain with intercourse, interference in athletic activities, previous obstetric or straddle injury, reversing female genital cutting, vaginal prolapse, incontinence, or gender affirmation surgery) are not medically indicated, pose substantial risk, and their safety and effectiveness have not been established. So there you have it, an in depth analysis of the latest “state-of-the-art” opinion written by a group with no experience in cosmetic gynecology. Judging by the fact that their first and only previous publication on the topic happened over 12 years ago, and that contemporary cosmetic gynecology has been around for over 20 years and is now a growing field globally, one would not be out of place in characterizing their behavior as reactive. Reactive as in “devoid of innovation”. Reactive as in full of agenda. A pernicious agenda. Clearly, they do not have their finger on the pulse of the state of the art. One should concerned, seriously concerned whenever an entity with a reputation for expertise in one area, with a reputation for publishing quality information goes off-brand off-the-rails and off-message on a poorly constructed alarmist rant about a topic on which they lack expertise. I hope you feel empowered and enlightened. ____________________________________ I'm most easily reached at DrMarcoPelosi.com

2 Comments

Cristo Papasakelariou MD, master pelvic surgeon from Houston, Texas, reviews the principles and demonstrates the surgical approaches to rectovaginal fistula repair. A great review for all cosmetic gynecologists from the ISCG archives. Recorded September 29, 2011, at the ISCG World Congress of Cosmetic Gynecology, Las Vegas, Nevada.

If you like this, check out all our World Congress lectures, conferences and congresses online here: https://vimeo.com/iscg/vod_pages

Dr Marco Pelosi III speaks to RealSelf about vaginoplasty with Dr Michelle Owens re-enacting the role of the interviewer. The article is geared to patient-centric concerns.

Just as the physically disabled adjust their mental processes to accomplish tasks designed for the typical human "package", so too must the 21st century surgeon adapt their thought patterns to evolve beyond the limitations of operations designed when the Enhanced Surgeon did not exist.

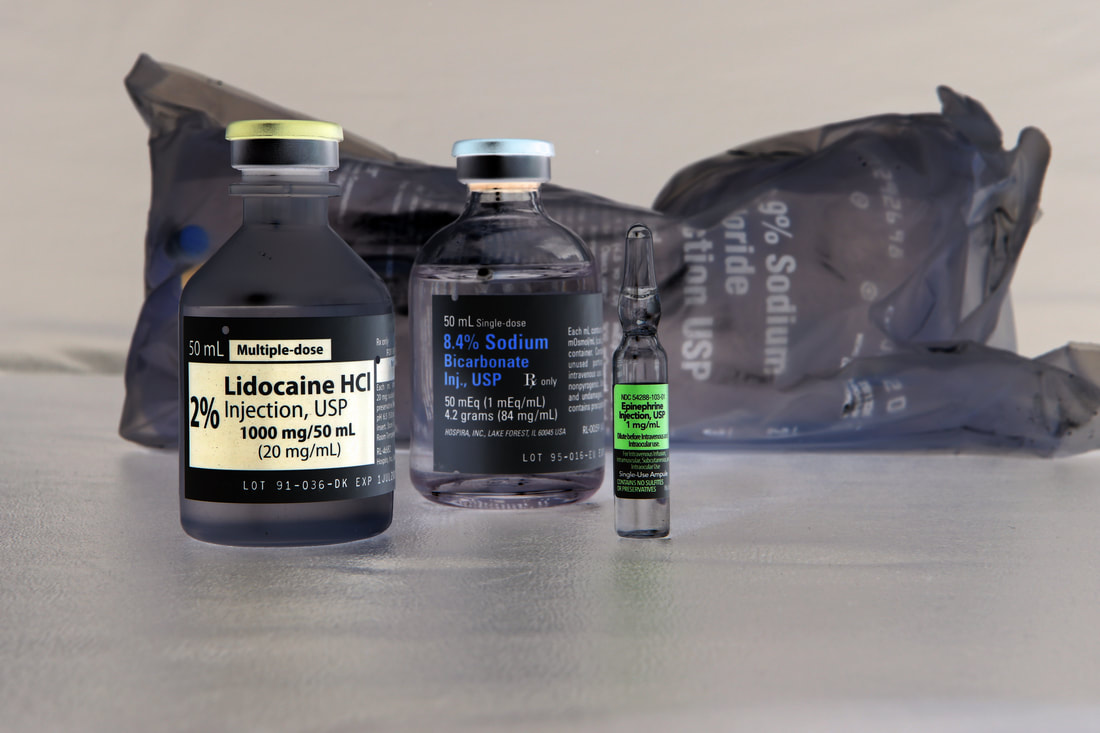

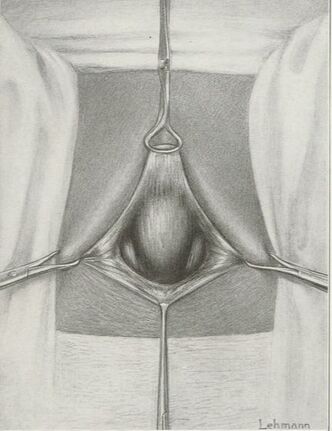

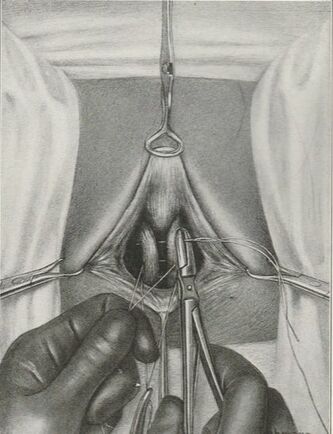

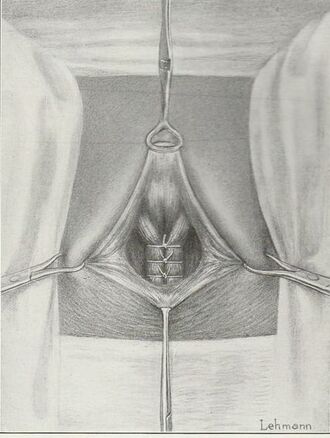

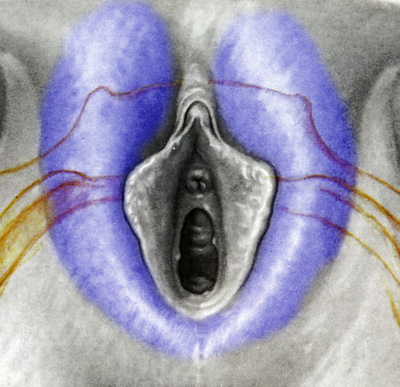

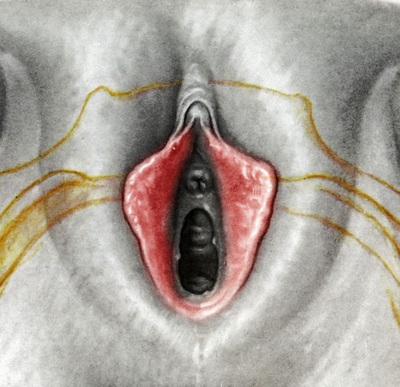

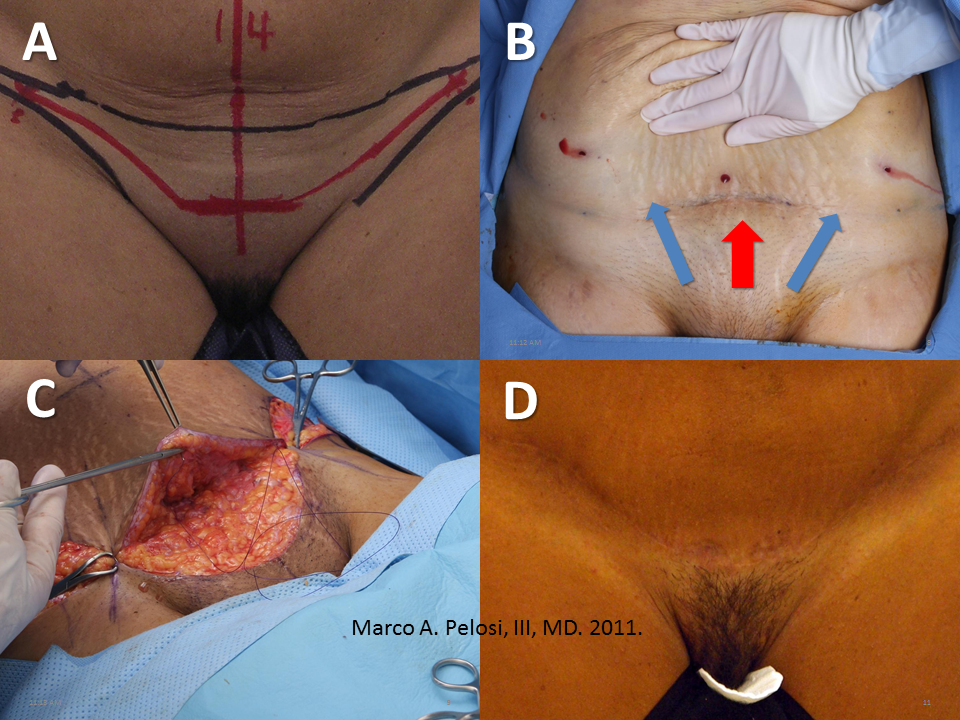

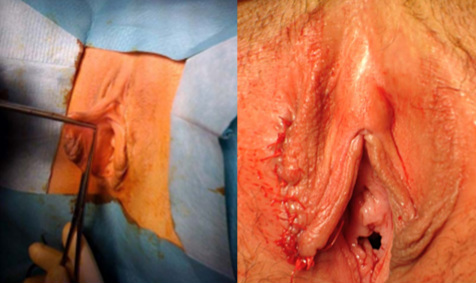

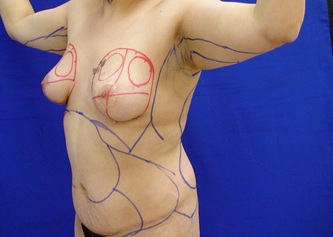

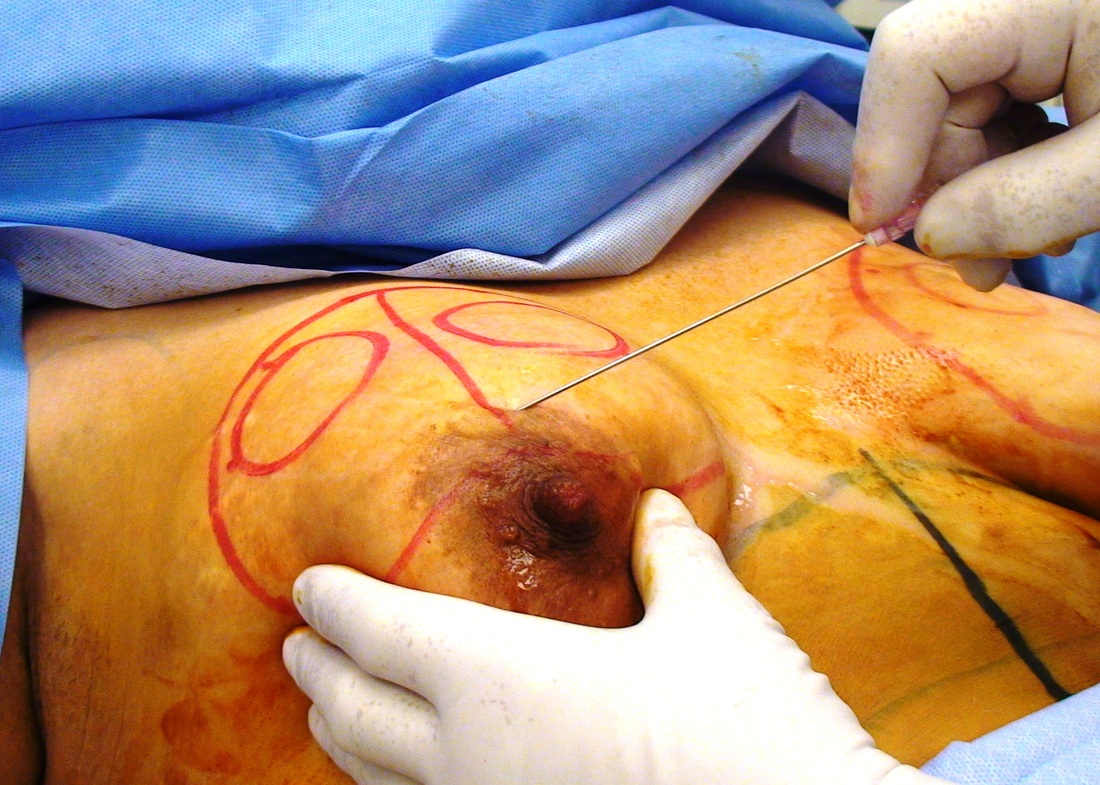

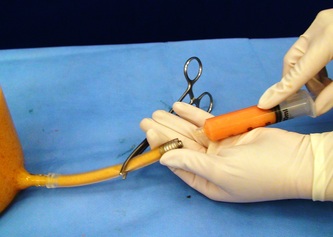

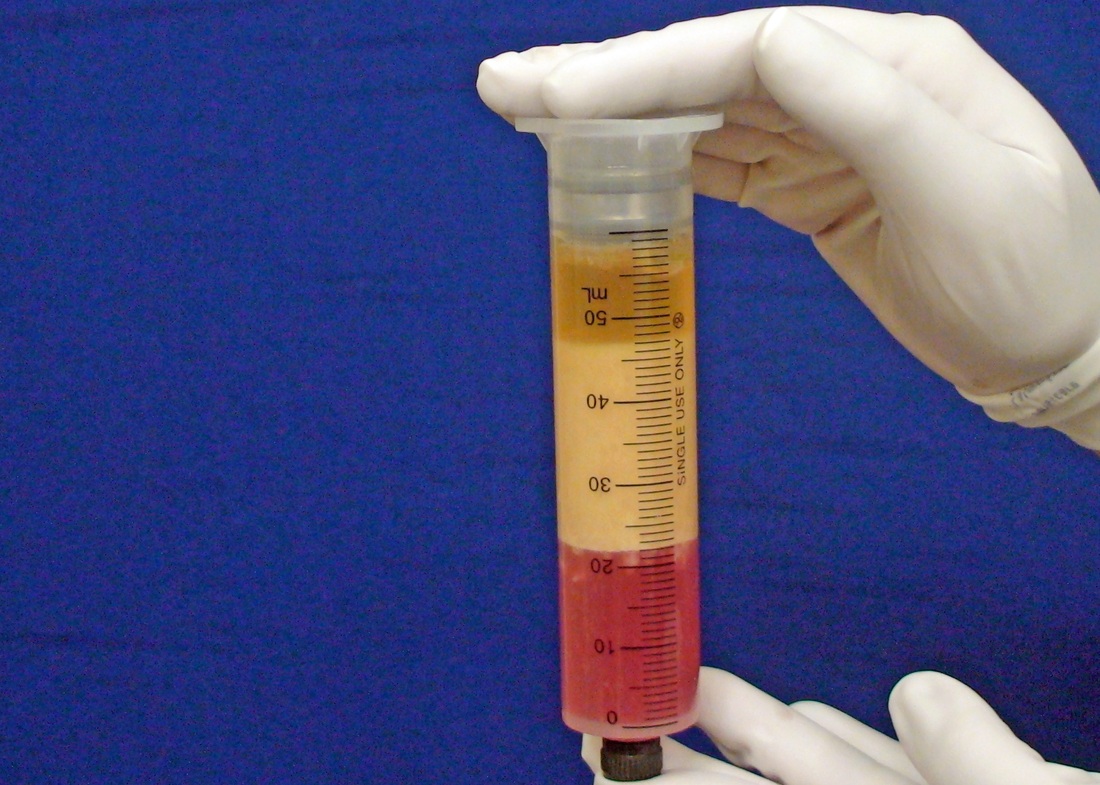

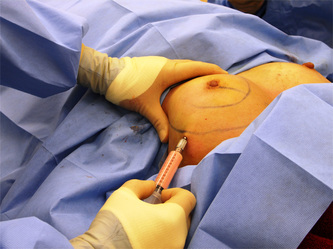

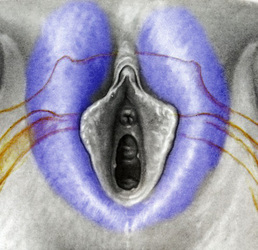

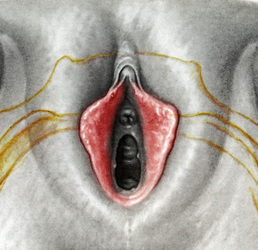

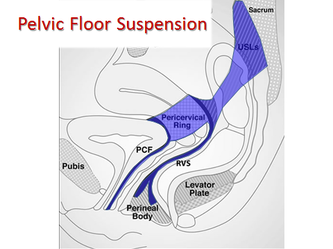

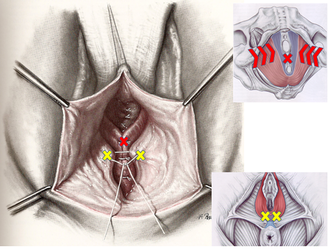

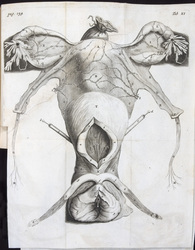

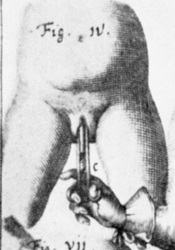

Tranexamic acid is the latest adjunct in cosmetic surgery for the reduction of bleeding, bruising, and postoperative swelling. Popular in the oral form (Lysteda) as a treatment for heavy menses since the 1980s, and the intravenous form (Cyklokapron) in cardiovascular and orthopedic surgery for the control of surgical hemorrhage for decades, it has also been used effectively by direct application to the surgical field by irrigation, soaked pledgets and tissue injection in hair transplantation and various aesthetic procedures of the face, breasts, and abdomen including liposuction. We have been using topical tranexamic acid in blephoroplasty, breast augmentation, abdominoplasty, liposuction, and abdominoplasty, and vaginoplasty for the past year with similar positive findings to those of recent authors. There is no precedent in vaginoplasty to the best of our knowledge. How we use tranexamic acid in cosmetic gynecologyA wide range of effective dosages for topical tranexamic acid is reported in the literature. Our most common application is in liposuction and the dosage we have been using for this procedure is 500mg tranexamic acid per liter of tumescent local anesthesia (TLA). We have used the same dose for all other applications including vaginoplasty. The method of topical application has been direct tissue injection at the time of local anesthesia infiltration and TLA-soaked surgical sponges. In the vaginoplasty example above, the right sided puborectalis muscle (medial border inked) is about to be injected with Tranexamic-TLA in preparation for levatorplasty. A midline pleated rectocele repair has been completed and the suture line is obvious centrally. Notice the excellent hemostasis of the entire field despite the extent of the dissection. Same operation after completion of a three-layer continuous levatorplasty. There is no bleeding from the puborectalis suture line. This means less postoperative swelling, inflammation and discomfort. Same operation at final stage (perineal reconstruction) showing hemostasis of the deep transverse perineal muscles (inked), superfical perineal muscles, and bulbocavernosus. The surgical sponge in the vaginal canal is serving as a temporary scaffolding for contour adjustment purposes, not for hemostasis. What precautions need to be taken when using tranexamic acid?Tranexamic acid is excreted through the kidneys. Patients must have normal renal function. Also, the concomitant use of oral contraceptives or a history of thromboembolic disease are contraindications to the use of tranexamic acid. The use of tranexamic acid has not been found to increase the surgical risk of thrombembolic disease. How does tranexamic acid work?This post was written as a practice pearl, recipe-style. You can delve into the mechanisms of action of tranexamic acid here. In brief, tranexamic acid keeps newly-formed blood clots from being broken down (fibrinolysis) by inhibiting plasmin.

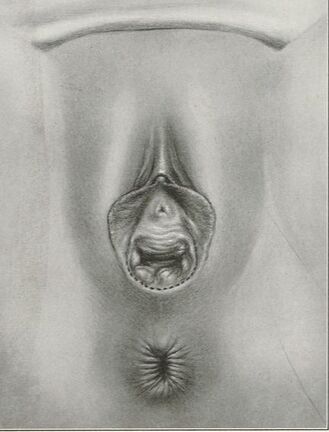

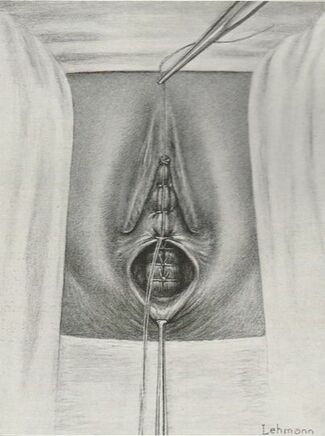

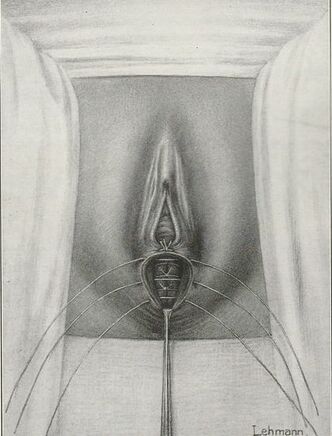

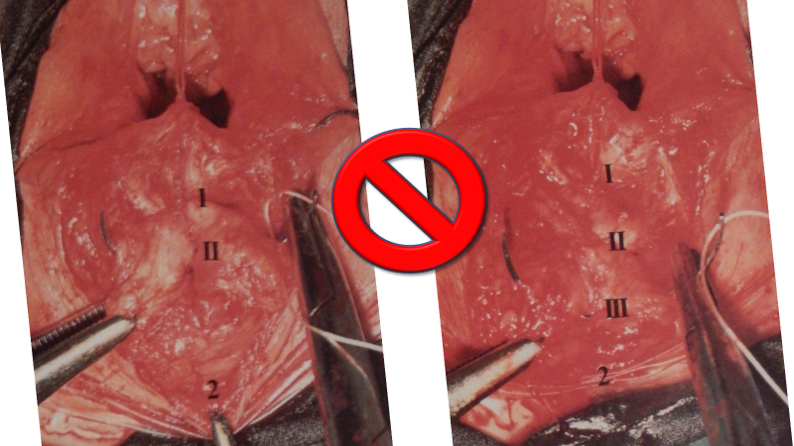

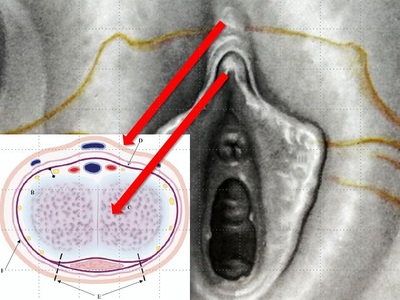

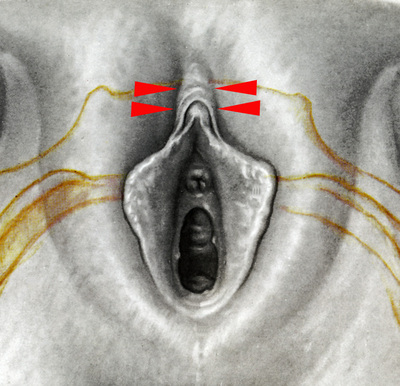

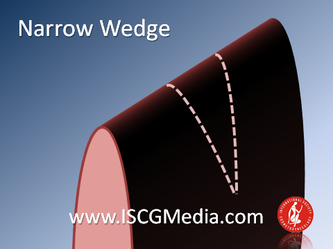

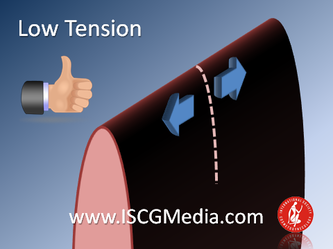

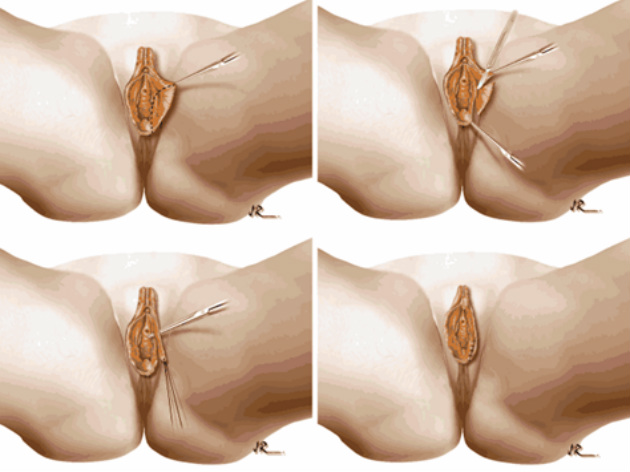

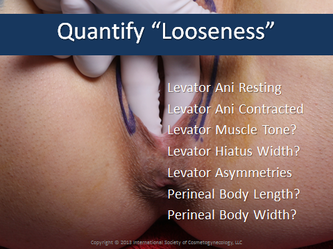

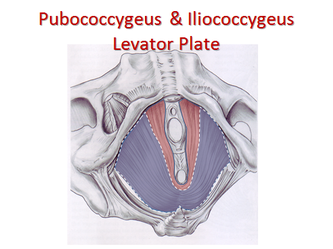

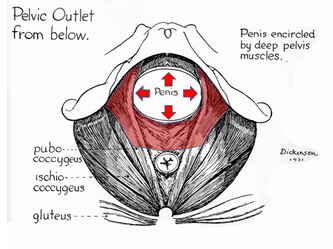

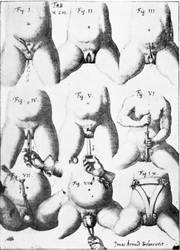

They say levatorplasty is wrong. They say levatorplasty causes painful sex. They point to ancient literature and say, "there's the proof". They write new articles referencing the ancient literature and say, "look, there's more proof - it's in the references". I say they're wrong. Not about the accuracy of what they referenced. I've read the ancient literature, the modern literature, and everything in between. I've been performing levatorplasties for over two decades. My patients aren't experiencing the painful sex that my contemporaries have referenced and the Ancients have described. What's going on here? A review of the history of levatorplasty indicates clearly that their levatorplasty and my levatorplasty are not the same. A review of the ancient "proof" of levatorplasty-induced sexual pain (dyspareunia) reveals that these procedures were overaggressive in certain respects and incomplete in others. For the uninitiated, levatorplasty or more accurately, anterior levatorplasty is the practice of suturing the medial-most portion of the levator ani fibers (a section of the muscle called the puborectalis) immediately proximal to the anal sphincters across the midline and advancing this plication proximally, This is usually done through a perineal incision extended to the posterior vaginal wall. The practice of levatorplasty was introduced by Robert Ziegenspeck of Germany in 1900. To understand the problem with the "wrong" techniques of levatorplasty, we need to go back one hundred years ago and examine the work of Arnold Sturmdorf: In 1919, the influential and innovative Arnold Sturmdorf of New York, published and illustrated his technique of levatorplasty in his book, Gynoplastic Technology. His approach to muscle plication was incorporated by almost all techniques that followed. Sturmdorf's levator "myorrhaphy" begins with a horizontal incision at the introitus and a peeling of the posterior vaginal wall cephalad without additional incision of the flap. This exposes the rectocele defect centrally and the medial borders of the levator ani (puborectalis). No tissue is excised. No suturing is done on the rectocele bulge. Sturmdorf describes the plication, "The sutures passed entirely round (not through) the muscle-shanks, encircling them so as to secrure the broadest possible side-to-side surface contact under the vaginal floor." The procedure concludes with a longitudinal closure of the horizontal skin incision. No skin is excised. It is clear that the levator plication sutures are extremely broad and deep. The complete "encirclement" of these muscles and ligation places extreme tension on a large mass of tissue. This will undoubtedly cause ischemia and ischemia will cause significant discomfort in the short term. In the long term, chronic tension on the muscle tissue will predispose to myalgia and traction pain on nerve fibers. The absence of an independent repair of the rectocele bulge creates two problems. First, it places all of the tension of subsequent bowel movements directly onto a single plane of tissue placing additional stress centrally. It would surprise no one that this type of levatorplasty would create pain with sex or any activity that stresses the muscle tissue. Second, it leaves the low-pressure tissue of the rectocele hernia floating, in essence, and free to float cephalad beyond the plication zone and recur later. The most recent of the oft-quoted articles on painful levatorplasty articles was published by Kahn and Stanton in 1997 (BJOG.1997;104:82-86.). They looked retrospectively at 209 British women treated for rectocele using Stanton's mid-century levatorplasty-only method. Painful sex or anatomical difficulty with sex was found in 27 percent, although 18 percent had problems beforehand. Stanton stated that his levatorplasty technique was identical to that of his British colleagues, Lees and Singer (pictured above). The huge needle bites through a large mass of levator muscle tissue indicate an aggressive high-tension approach. The photos also reveal that the rectocele itself is not sutured. Like that of Sturmdorf, this method provokes tension-related issues. In their discussion, Kahn and Stanton opine that dyspareunia is caused by levatorplasty because of "pressure atrophy of the included muscle fibers and subsequent scarring." citing references from the 1920s, but no data (Goff. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1928;46:855-866). So where does this historical analysis lead us? First, we see that taking huge bites of the levator ani muscle and forcing them together under high tension creates problems. Second, we see that using a single layer of muscle tissue as the only repair for a rectocele creates problems. Third, we see that quoting articles that quote articles doesn't provide data directly and that opinions in the discussion section of published articles aren't exactly the same thing as evidence and might distort the impression of the literature for those who fail to dig a little deeper. I stated that my levatorplasty is not the same as "their" levatorplasty. What's the difference?

It doesn't require huge bites of muscle tissue. It doesn't involve high tension. And it doesn't take place withouit the support of a sturdy rectocele repair underneath to take the tension and stress off the sensitive muscle tissue. Two decades. No problems. No kidding. Would you like to learn more?

Listen to the Expert Panel Discussion from the 2019 ISCG World Congress of Cosmetic Gynecology conducted on January 29, 2019, in Orlando, Florida. Nine world experts with extensive experience in the use of nonsurgical lasers and radiofrequency devices discuss the concerns raised by the FDA regarding the use of these technologies and share their insights and experience. Moderator: Marco A. Pelosi, III, MD. Expert Discussants: Alexander Bader, MD (UK), Rafal Kuzlik, MD, PhD (Poland), Michael Krychman, MD (USA), Michael Goodman, MD (USA), Oscar Aguirre, MD (USA), John Miklos, MD (USA), Red Alinsod, MD (USA), Adrian Gaspar, MD (Argentina), Jorge Gaviria, MD (Venezuela & Spain).

This article was originally published on LinkedIn on August 30, 2018. I just got off the phone from two calls. The first was a surgeon seeking vaginal rejuvenation training and the second was a patient seeking a vaginal rejuvenation procedure. They sought my expertise on two completely different things. The never-been-lucid definition of vaginal rejuvenation is growing in many directions unimagined in years past. On a regular basis, it takes twists and turns as educated proponents, ignorant proponents, and detractors add narrative- and agenda-loaded meanings to this volatile term.

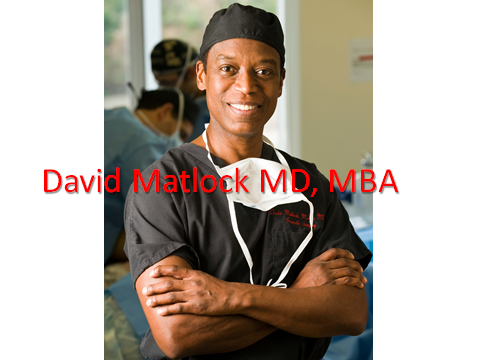

Why is this happening? I see a few major reasons: Foremost is large-scale marketing. Second, is the catalytic effect of social media on a level unknown when the first iteration of vaginal rejuvenation made its debut in the late 1990s. A public whose sole education on the term arises from repetitive marketing to their smartphones and whose knowledge of their bodies appears quite limited has no filter with which to distill whatever the Oprahs and Dr. Ozs of the world feed them via colorful Hollywood-quality vignettes. Their “research” is overwhelmingly a collection of marketing materials dressed up with pseudoscience. It’s time to separate fact from fiction. The Backstory Vaginal childbirth has been has been destroying vaginas since the beginning of time and modern pelvic floor research has been confirming what mothers have known for generations. Focus has been on the vaginal supports, bladder and bowel dysfunctions, and prolapse. Curiously, vaginal laxity is excluded from this conversation in medical circles, in the gynecologic literature and at meetings of large academic gynecologic societies. I invite you to search the term “vaginal laxity” on the websites of ACOG and FIGO, the two largest gynecologic academic societies in the world and that of AUGS, the largest urogynecologic society in the world to witness this void personally. I have yet to find a female patient who states that sex improved after vaginal childbirth. These women have gynecologists who deliver babies every day. Many gynecologists are mothers themselves. They see the vaginal trauma of childbirth day in and day out and experience the aftermath personally. Sadly, I would have trouble swinging a cat in a room full of academic gynecologists without hitting an opponent to the concept that tightening the vagina might improve sex after vaginal childbirth. You can live without treating it. It’s a lifestyle issue they say. True. That was the world pre-1996. But what else can we live without treating – fertility, infertility, unwanted pregnancy, foreskins. All of the latter are essentially lifestyle issues on which the specialty is deeply rooted. The Day Sex Got Better A patient underwent gynecologic anterior and posterior vaginal repairs for medical indications in Beverly Hills, California, in 1996. A few months later she told her surgeon, David Matlock, that her sex life had also improved; she said that it was because her vagina felt tighter. She referred a friend to him for the same operation. She had no medical indications, but she had a lax vagina that she wanted tighter to improve her sex life too. Dr. Matlock acceded to the request. Her sex life improved. Vaginal rejuvenation was born. (ref: conversation with Matlock, 1999) David Matlock, MD, became David Matlock, MD, MBA. In the process, he learned about marketing, intellectual capital, and trademarks. In 1998, he labelled his operation Laser Vaginal RejuvenationTM and added Designer Laser VaginoplastyTM (a labiaplasty procedure despite the name), and the G-shotTM (a dermal filler injection for the G-spot) to his repertoire. Why Laser? Two reasons: Matlock preferred the laser scalpel to the steel scalpel for his anterior and posterior repairs having learned to use the technology in his residency training. Lasers were introduced to the field of gynecology in the early 1970s and were a topic of intense academic and private practice interest and study well into the 1980s and 1990s. Second reason: To this day, “laser” has unparalleled marketing power to patients. A Bodacious Adolescence When you launch Laser Vaginal Rejuvenation in the epicenter of aesthetic culture and entertainment media, it gets noticed. Matlock became a global celebrity. Women added Laser Vaginal Rejuvenation to their Mommy Makeover bucket lists and other surgeons, naturally, wanted in on the action. Matlock saw the potential market and created the Laser Vaginal Rejuvenation Institute of America to train surgeons in his techniques and license his trademarks. He utilized a franchise model and Laser Vaginal Rejuvenation began its widespread growth. Competitors emerged and, unable to use the trademarked terminologies, created their own nicknames for their versions of these procedures. The most common of these was simply vaginal rejuvenation. The End of the Beginning Gynecologic academia had consistently stayed out of the aesthetic/cosmetic arena and periodically reaffirmed this stance in public statements. However, the emergence of social media (Facebook 2004, YouTube 2005, Twitter 2006, iPhone 2007) created a wave of global attention on vaginal rejuvenation on which the academics were forced to offer commentary. In September 2007, the prominent American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) released ACOG Committee Opinion No. 378: Vaginal "Rejuvenation" and Cosmetic Vaginal Procedures – a document which was parroted by academic societies around the world. A brief five paragraphs and one reference long, this document has been misquoted, misinterpreted and misused widely by people at all levels of intelligence ever since it came out. The opinion attempts to define vaginal rejuvenation, yet opens with the admission that the authors are unclear of the exact nature of the procedures upon which they are opining. It lists Dr. Matlock’s trademarked portfolio procedure-by-procedure sans the word “laser,” yet they neither interviewed Matlock nor observed his work (ref: conversation with Matlock 2007; conversation with ACOG committee members 2008). The second paragraph reiterates the trademarked terminology, questions its safety and effectiveness, and adds that it lacks data. Perhaps, if they had learned that Laser Vaginal Rejuvenation was an alias for gynecologic vaginal repairs with over a century’s worth of robust data, they might have concluded differently. The third paragraph disparages the businesses of franchising, marketing, and paying for education. This is a direct objection to Matlock’s business model, but it didn’t apply to anyone else in the vaginal rejuvenation arena. Hypocritically, most if not all college and postgraduate educational programs require payment to the educators and most if not all academic societies, ACOG included, demand annual fees for the right to use their letters of distinction. The fourth paragraph is best characterized as The Insanity Plea: a woman requesting these procedures needs a long talk to convince her that she’s normal. The lone reference in entire opinion is attached to this paragraph - a study that found that labia minora came in different shapes and sizes in 50 British women. The concluding paragraph complains that women are being misled, that the procedures are not routine, reiterates the lack of data misconception, and out of thin air adds a list of potential complications that may arise from procedures on which the authors already stated they are unclear. The Rise of the Machines For the first decade and a half of it’s existence, vaginal rejuvenation was a surgical procedure for vaginal tightening with a steep barrier to entry - expertise in internal vaginal surgery – skills limited to gynecologists, urogynecologists, and some urologists. Then, the game changed. Beginning in 2009, pioneering gynecologists in Argentina and Italy began developing techniques for nonsurgical laser treatments of the vagina aimed initially at vaginal atrophy. Working in conjunction with the industry’s standard laser platforms, they devised equipment and protocols for fractional carbon dioxide laser ablation based on existing dermatology protocols. Over the next few years, other groups began clinical investigations into the treatment of urinary incontinence and vaginal laxity working with a variety of lasers. This era culminated with the entry of Deka (MonaLisa) and the Alma (FemiLift) CO2 lasers for noninvasive vaginal ablation into the US market in late 2014. From then until now, the market has literally exploded and almost every major laser manufacturer makes a vaginal probe for their platform and radiofrequency technologies have followed suit. The Marketing Paradox How do you market a vaginal laser in the US? This was the challenge for the industry in 2014. Most lasers owners were plastic surgeons, dermatologists and other aesthetic professionals who hadn’t done a pelvic exam since medical school. All of the applications for vaginal lasers to date were purely gynecologic in nature – atrophy, incontinence, and laxity, but most gynecologists weren’t early adopters and wouldn’t buy a laser unless they were sure of a steady market for the service and saw homegrown proof of its efficacy from experts in the field irrespective of the overseas experience. Marketing took a two-pronged approach: For existing aesthetics based laser owners, the theme became nonsurgical vaginal rejuvenation to get a piece of the vaginal laxity market and leave the rest to the gynecologists. For gynecologists, it was marketed first to academically inclined urogynecologists to establish credibility of efficacy. Since many in the gynecologic academic community had been mentally “poisoned” to the term vaginal rejuvenation in 2007 and eschewed any mention of vaginal laxity treatments, vaginal atrophy and urinary incontinence were the exclusive focus. For patients, the terms vaginal health and feminine health were created for direct marketing. Mass Confusion Wins By mid-2015, gynecologists and non-gynecologists alike were marketing laser vaginal rejuvenation, vaginal rejuvenation and nonsurgical vaginal rejuvenation online as synonyms for a variety of surgical and nonsurgical procedures well beyond the original meaning and intent of Matlock’s vaginal repairs. To confound matters further, patients doing online research on incontinence and vaginal atrophy were finding themselves in the offices of non-gynecologists without the benefit of a gynecologic assessment. The confusion persists to this day and continues to worsen as the number of devices and treatments continue to grow. At the present time, vaginal rejuvenation has so many possible meanings that it has no specific meaning. When a woman tells me that she wants vaginal rejuvenation today, I have absolutely no idea what the term means to her and what issues she is seeking to address. It might be a gynecologic issue. It might be an aesthetic issue. It might be surgical. It might be nonsurgical. I also have no idea what her expectations might be as her judgement may have been seriously clouded by whatever “research” she has chosen to believe. Vaginal rejuvenation in 2018 is a conversation starter, an icebreaker. The challenge in the conduct of this conversation is to understand that the average patient is clueless about her body, jaded with the expectations of mass media marketing hype, and completely at the mercy of the physician’s ethical compass. This article was originally published on LinkedIn on August 17, 2018. Recently, the MAUDE database has been cited as a source of “numerous” reports of adverse events associated with the use of transvaginal energy-based devices (tv-EBD). However, those who have cited the MAUDE database have failed to provide specifics regarding the quality, the quantity, and the nature of these reports. Seeking to satisfy my own curiosity, I conducted a search of the MAUDE database for adverse events for every vaginal EBD device and every manufacturer of such devices since they first appeared on the market in late 2014.

The search was conducted online via the FDA’s MAUDE search engine page. The name of each manufacturer, US distributor where relevant, and device was searched individually from 2014 to the present. The number of reports parameter was set to 500, the maximum. Some events had been reported more than once – some by personnel associated with manufacturers, some by physicians, some by patients. I then classified each device by it’s technology: Radiofrequency (RF), Radiofrequency with Active Cooling (RFAC), Carbon Dioxide Laser (CO2), Diode Laser (D) Erbium:Yag Laser (ER), Erbium:YAG + Diode Laser (ERD). These are the results of this search: Alma Lasers: FemiLift (CO2): no adverse events reported BTL Aesthetics: Ultra Femme 360 (RF): no adverse events reported Venus Concept: Fiore (RF): no adverse events reported Inmode: Votiva (RF): no adverse events reported Eufoton: LadyLift (D): no adverse events reported Cutera: Juliet (ER): no adverse events reported Lasering-USA: V-Lase (CO2): no adverse events reported Syneron CO2RE Intima (CO2): no adverse events reported Thermi: Thermiva (RF): 1 report: Gynecologist bruised her patient with device Cynosure: DEKA: MonaLisa Touch (CO2) 3 reports of 1 event dated 3/31/2016 of UTI symptoms after treatment by gynecologist 3 reports of 1 event dated 8/23/2017 of urethral pain after treatment #3 by urologist in patient with hx of chronic urethral pain before tx, positive response with first 2 treatments 2 reports of 8/10/2017 & 9/4/2017 of 1 event: physician burned his own hand b/c assembled laser improperly 1 report 2/11/2016 of pt who had pain after treatment by gynecologist and had medical treatment at local urgent care clinic with vaginal creams and oral pills Sciton: DiVa (ERD): 1 report of two non-physician medical staff who gave each other external burns unsupervised event 2/20/2018 Viveve: Geneveve (RFAC): 2 reports of 1 event: patient experienced multiple symptoms with “trial” handpiece after popping noise Lumenis: FemTouch (CO2): 1 report of patient getting eye infection from eye protection after treatment by gynecologist 1 event of issues cleaning the handpiece The total number of reports in this search was 15. The total number of events was 9. Two of these were non-physicians burning themselves while "playing doctor" with a laser. The total number of events involving patients undergoing treatment was 6. One of these was an eye infection from dirty eye protectors. This leaves 5 relevant events of vaginal issues. Let’s examine these five adverse events involving patients undergoing vaginal treatments with energy based devices. 1. The Thermiva RF bruise event: In 2016, a woman noticed discomfort after treatment by an unspecified operator then went to her gynecologist who diagnosed bruising. Bruising is not a known complication of any low temperature radiofrequency technology used in the vagina, but it is a common occurrence with excess pressure on the vulvovaginal area. I would suspect the latter. The procedure itself involves a gentle massaging motion of a plastic handpiece and does not involve the application of excess pressure. 2. The MonaLisa UTI event: In 2016, a woman noticed urethral burning and discomfort beginning two days after treatment by her gynecologist and persisting for several weeks. Although urinalysis was performed 3 times, no urine culture was performed and no antibiotic therapy was given. The risk of urinary tract infection exists with any manipulation of the vulvovaginal area and is not unique to any procedure or any device. Procedures in the vagina and vulva are categorized as Class II: Clean Contaminated by the CDC with an infection rate of 4 to 10 percent (ref). Up to 20 percent of UTIs have been reported to show a negative urinalysis and culture is the gold standard (ref). One of the 3 reports of this event states that this patient had an active yeast infection that was being treated at the time of her procedure. 3. The MonaLisa urethral pain event: In 2017, a urologist attempted to treat the symptom of chronic urethral pain with CO2 laser fractional ablation. The patient’s symptoms vacillated in response to treatment and overall there was no long term detrimental effect documented. The main issue here was lack of knowledge in the techniques, technology and indications. There is no literature anywhere to support the use of fractional CO2 laser ablation to treat urethral pain and there is no protocol for doing so. This is an example of experimentation. 4. The MonaLisa post-procedure discomfort event: In 2016, A woman experienced discomfort after her procedure and went to an urgent care clinic to have her issue addressed. This report was provided by the manufacturer and was reported because the patient sought and received care from an urgent care clinic. It is not uncommon for patients to seek out care at urgent care clinics. Reasons for doing so may include inadequate pre/post procedure counseling, an inability to contact their treating physician, the suggestion of friend or family member, or convenience. 5. The Geneveve pain event: In 2017, a non-gynecologist treated a woman who had never undergone the procedure before at twice the standard energy dose with a “trial” handpiece that hadn’t been used before. A strange “popping” noise was documented during the procedure, but the procedure was continued. The patient reported pain, sensation issues and urinary incontinence. This event suggests a complete lack of professional judgement and a lack of knowledge of energy based devices on the part of the operator. Although I have no experience with the use of this product, I have 27 years of experience with lasers. Every laser case invokes a strict checklisted laser protocol that involves equipment checking and test firing outside the human body. The latter applies to equipment that is in it’s final form, not a trial device. In the case of a trial device, a trial procedure is done outside the human body on a suitable model where the device can be tested. At that stage, it might be ready for a human trial or not. It is not offered as reasonable treatment to anyone as this is purely experimentation. Arbitrarily doubling the energy dose in a treatment-naïve patient is without precedent in any energy-based therapeutic intervention that I am aware of and cannot be justified. Ignoring an inexplicable noise during operation of the device is unfathomable. This unfortunate event can be deemed a compounding of errors stemming from extremely poor clinical judgement. This analysis of the MAUDE database brings several issues to light. First, is the need to distinguish the number of events from the number of reports of singular events. Every year, my birthday is reported “numerous” times by my Facebook friends. This happy birthday effect does not elevate the magnitude of this singular event. Second, is the need to educate “rookies” to EBD in the technologies they are using, to the indications of the treatments they are providing, and to the counseling and postprocedural support that their patients may require. All of these five adverse events can be classified as human factor errors. My colleagues from other specialties suggest that I am inciting a turf war. To the contrary, I am offering simple advice for staying out of trouble. So many “skin experts” that I know offer elaborate skin imaging and mapping technologies prior to facial EBD treatments, yet offer no vaginal assessment whatsoever prior to firing a laser or other EBD in the vaginal canal blindly. Third, is the need to establish a collective database of experience with the devices. The MAUDE system does not and cannot track the number of procedures performed. It can only offer a glimpse into the issues of reported events and it is severely limited at that. When estimating the unknown frequency of true adverse events, pundits against EBD will exaggerate the numerator and dwell on the few available sad vignettes while those who favor EBD will stress that there is no denominator, but that it’s probably large. This article was originally published on LinkedIn on August 5, 2018. One week ago, tomorrow, the FDA issued a Safety Communication slamming the use of energy-based devices for the indications of "vaginal rejuvenation" - "an ill-defined term" - "sometimes used to describe non-surgical procedures intended to treat vaginal symptoms and/or conditions including, but not limited to:

Vaginal laxity Vaginal atrophy, dryness, or itching Pain during sexual intercourse Pain during urination Decreased sexual sensation" The document stated that there are two problems: 1. "To date, we have not cleared or approved for marketing any energy-based devices to treat these symptoms or conditions, or any symptoms related to menopause, urinary incontinence, or sexual function." 2. "The treatment of these symptoms or conditions by applying energy-based therapies to the vagina may lead to serious adverse events, including vaginal burns, scarring, pain during sexual intercourse, and recurring/chronic pain." The document lists two references: